what step did the nra take to restore the nations economy

NRA Blueish Eagle poster. This would be displayed in store windows, on packages, and in ads. | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1933, by the National Industrial Recovery Deed (NIRA) |

| Dissolved | May 27, 1935, past courtroom case Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States |

The National Recovery Administration (NRA) was a prime agency established by U.Southward. president Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) in 1933. The goal of the assistants was to eliminate "cut pharynx competition" past bringing industry, labor, and regime together to create codes of "fair practices" and fix prices. The NRA was created past the National Industrial Recovery Human action (NIRA) and allowed industries to become together and write "codes of fair contest." The codes intended both to help workers gear up maximum wages and maximum weekly hours, as well as minimum prices at which products could be sold. The NRA besides had a two-year renewal charter and was set to elapse in June 1935 if not renewed.[i]

The NRA, symbolized by the Blue Hawkeye, was popular with workers. Businesses that supported the NRA put the symbol in their shop windows and on their packages, though they did non always go along with the regulations entailed. Though membership of the NRA was voluntary, businesses that did not display the eagle were very often boycotted, making information technology seem mandatory for survival to many.

In 1935, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously declared that the NRA police force was unconstitutional, ruling that it infringed the separation of powers under the United States Constitution. The NRA quickly stopped operations, but many of its labor provisions reappeared in the National Labor Relations Act (Wagner Act), passed later the same twelvemonth. The long-term result was a surge in the growth and power of unions, which became a cadre of the New Deal Coalition that dominated national politics for the adjacent three decades.

Background [edit]

Every bit part of the "First New Bargain," the NRA was based on the premise that the Swell Depression was acquired by market place instability and that regime intervention was necessary to balance the interests of farmers, business and labor. The NIRA, which created the NRA, declared that codes of fair contest should exist developed through public hearings, and gave the Administration the power to develop voluntary agreements with industries regarding work hours, pay rates, and price fixing.[two] The NRA was put into operation by an executive order, signed the same day equally the passage of the NIRA.

New Dealers who were office of the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt saw the close analogy with the earlier crunch handling the economics of World War I. They brought ideas and experience from the government controls and spending of 1917–xviii.

In his June 13, 1933 "Statement on the National Industrial Recovery Act," President Roosevelt described the spirit of the NRA: "On this idea, the offset part of the NIRA proposes to our industry a bully spontaneous cooperation to put millions of men back in their regular jobs this summer."[three] [iv] He further stated, "Only if all employers in each merchandise now band themselves faithfully in these modern guilds—without exception—and agree to act together and at one time, none volition exist hurt and millions of workers, then long deprived of the right to earn their staff of life in the sweat of their labor, tin raise their heads over again. The challenge of this law is whether nosotros can sink selfish interest and present a solid front end confronting a common peril."[3] [four]

Inception [edit]

The motion picture manufacture supported the NRA

The first director of the NRA was Hugh S. Johnson, a retired United States Regular army general who had been in accuse of supervising the wartime economic system in 1917-1918. He was named Time magazine's "Man of the Yr" in 1933. Johnson saw the NRA equally a national crusade designed to restore employment and regenerate manufacture.

Johnson called on every business establishment in the nation to take a stopgap "coating code": a minimum wage of between 20 and 45 cents per hr, a maximum workweek of 35 to 45 hours, and the abolition of child labor. Johnson and Roosevelt contended that the "blanket code" would raise consumer purchasing ability and increase employment.

Historian Clarence B. Carson noted:

At this moment in time from the early days of the New Deal, it is hard to recapture, even in imagination, the heady enthusiasm among a goodly number of intellectuals for a government planned economic system. So far as can now be told, they believed that a bright new day was dawning, that national planning would result in an organically integrated economy in which everyone would joyfully piece of work for the mutual good, and that American society would be freed at concluding from those antagonisms arising, equally General Hugh Johnson put it, from "the murderous doctrine of savage and wolfish individualism, looking to canis familiaris-eat-dog and devil take the hindmost.[5]

Goal [edit]

The negotiations of a code for the bituminous coal industry came against the background of a rapidly swelling matrimony, the United Mine Workers headed by John 50. Lewis and an unstable truce in the Pennsylvania coal fields. The NRA tried to get the principals to compromise with a national code for a decentralized manufacture in which many companies were anti-union, sought to keep wage differentials, and tried to escape the commonage bargaining provisions of department 7A. Agreement amongst the parties was finally reached simply later on the NRA threatened that information technology would impose a code. The code did not constitute price stabilization, nor did it resolve questions of industrial cocky-regime versus governmental supervision or of centralization versus local autonomy, only it made dramatic changes in abolishing child labor, eliminating the compulsory scrip wages and visitor store, and establishing fair merchandise practices. It paved the way for an of import wage settlement.[six]

Price controls [edit]

In early 1935 the new chairman, Samuel Clay Williams, appear that the NRA would stop setting prices, but businessmen complained. Chairman Williams told them plainly that, unless they could prove it would damage business organisation, NRA was going to put an stop to price command. Williams said, "Greater productivity and employment would result if greater price flexibility were attained."[vii] Of the 2,000 businessmen on hand probably 90% opposed Mr. Williams' aim, reported Time magazine: "To them a guaranteed price for their products looks like a purple road to profits. A stock-still price to a higher place price has proved a lifesaver to more than than i inefficient producer."[seven] Withal, it was also argued NRA'south cost control method promoted monopolies.[8]

The business organisation position was summarized past George A. Sloan, head of the Cotton fiber Textile Code Dominance:

Maximum hours and minimum wage provisions, useful and necessary every bit they are in themselves, practise not forbid toll demoralization. While putting the units of an industry on a fair competitive level insofar as labor costs are concerned, they practice not forbid subversive toll cutting in the auction of commodities produced, any more than a fixed price of textile or other element of cost would prevent it. Destructive competition at the expense of employees is lessened, but information technology is left in full swing against the employer himself and the economic soundness of his enterprise....Only if the partnership of industry with Regime which was invoked by the President were terminated (equally nosotros believe it will non be), then the spirit of cooperation, which is one of the best fruits of the NRA equipment, could not survive.[7]

The Blueish Eagle [edit]

The Blue Eagle was a symbol used in the U.s. by companies to evidence compliance with the National Industrial Recovery Act. To mobilize political support for the NRA, Johnson launched the "NRA Blue Eagle" publicity campaign to boost his bargaining strength to negotiate the codes with business and labor.[9] [10] [11]

Many sources credit advertising art director Charles T. Coiner with the design.[12] [13] [14] [15] According to a few sources, however, it was sketched by Johnson, based on an idea used by the State of war Industries Lath during World State of war I.[16] [eleven] The hawkeye holds a gear, symbolizing industry, in its right talon, and bolts of lightning in its left talon, symbolizing power.[17]

All companies that accustomed President Franklin D. Roosevelt'south Re-employment Agreement or a special Lawmaking of Fair Contest were permitted to brandish a poster showing the Bluish Eagle together with the announcement, "NRA Fellow member. We Practise Our Part."[xvi] [10] [xi] Consumers were exhorted to buy products and services only from companies displaying the Blue Eagle imprint.[16] [11] According to Johnson,

When every American housewife understands that the Blueish Eagle on everything that she permits into her habitation is a symbol of its restoration to security, may God take mercy on the man or group of men who effort to trifle with this bird.[18]

Critics [edit]

Virtually businesses adopted the NRA without complaint, but Henry Ford was reluctant to join.[nineteen]

The National Recovery Review Lath, headed past noted criminal lawyer Clarence Darrow, a prominent liberal, was fix by President Roosevelt in March 1934 and abolished by him that same June. The board issued iii reports highly critical of the NRA from the perspective of small business organization, charging the NRA with fostering cartels. The Darrow board, influenced past Justice Louis D. Brandeis, wanted instead to promote competitive capitalism.[20]

Representing big business, the American Liberty League, 1934–40, was run by leading industrialists who opposed the liberalism of the New Bargain. Regarding the controversial NRA, the League was ambivalent. Jouett Shouse, the League president, commented that "the NRA has indulged in unwarranted excesses of attempted regulation"; on the other, he added that "in many regards [the NRA] has served a useful purpose."[21] Shouse said that he had "deep sympathy" with the goals of the NRA, explaining, "While I feel very strongly that the prohibition of kid labor, the maintenance of a minimum wage and the limitation of the hours of piece of work belong under our form of government in the realm of the diplomacy of the different states, even so I am entirely willing to agree that in the case of an overwhelming national emergency the Federal Regime for a limited period should be permitted to assume jurisdiction of them."[22]

The NRA in exercise [edit]

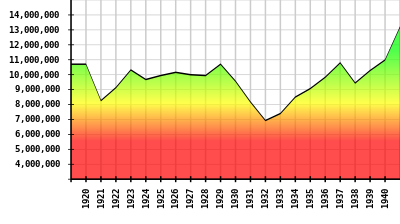

Chart three: Manufacturing employment in the United States from 1920 to 1940

The NRA negotiated specific sets of codes with leaders of the nation'south major industries; the most important provisions were anti-deflationary floors beneath which no company would lower prices or wages, and agreements on maintaining employment and production. In a remarkably short fourth dimension, the NRA won agreements from almost every major manufacture in the nation. According to some bourgeois economists, the NRA increased the price of doing business concern by forty pct.[23] Donald Richberg, who soon replaced Johnson every bit the caput of the NRA said:

There is no option presented to American business between intelligently planned and uncontrolled industrial operations and a render to the gold-plated anarchy that masqueraded as "rugged individualism."...Unless industry is sufficiently socialized by its private owners and managers and so that bully essential industries are operated under public obligation appropriate to the public interest in them, the advance of political control over individual industry is inevitable.[24]

Past the time it ended in May 1935, industrial production was 22% college than in May 1933.[ citation needed ]

Specific industries [edit]

Pennock (1997) shows that the safe tire industry faced debilitating challenges, mostly brought about by changes in the industry's retail structure and exacerbated by the Depression. Segments of the industry attempted to use the NRA codes to solve these new problems and stabilize the tire market, but the tire manufacturing and tire retailing codes were patent failures. Instead of leading to cartelization and higher prices, which is what most scholars presume the NRA codes did, the tire industry codes led to fifty-fifty more fragmentation and price cutting.[25]

Alexander (1997) examines the macaroni industry and concludes that cost heterogeneity was a major source of the "compliance crisis" affecting a number of NRA "codes of fair competition" that were negotiated by industries and submitted for government approval under the National Industry Recovery Act of 1933. The argument boils down to assumptions that progressives at the NRA allowed majority coalitions of small-scale, loftier-cost firms to impose codes in heterogeneous industries, and that these codes were designed by the high-cost firms under an ultimately erroneous conventionalities that they would be enforced by the NRA.[26]

Storrs (2000) says the National Consumers' League (NCL) had been instrumental in the passage and legal defense of labor legislation in many states since 1899. Women activists used the New Deal opportunity to gain a national forum. General Secretary Lucy Randolph Mason and her league relentlessly lobbied the NRA to make its regulatory codes just and fair for all workers and to eliminate explicit and de facto discrimination in pay, working conditions, and opportunities for reasons of sex, race, or matrimony status. Even after the demise of the NRA, the league continued campaigning for collective bargaining rights and fair labor standards at both federal and state levels.[27]

Enforcement [edit]

Virtually 23 million people were employed under the NRA codes. However, violations of codes became common and attempts were made to use the courts to enforce the NRA. The NRA included a multitude of regulations imposing the pricing and product standards for all sorts of goods and services. Individuals were arrested for not complying with these codes. For example, one minor businessman was fined for violating the "Tailor's Code" past pressing a suit for 35 rather than NRA required twoscore cents. Roosevelt critic John T. Flynn, in The Roosevelt Myth (1944), wrote:

The NRA was discovering it could not enforce its rules. Blackness markets grew up. Simply the nearly violent constabulary methods could procure enforcement. In Sidney Hillman's garment manufacture the code authority employed enforcement police. They roamed through the garment district like storm troopers. They could enter a man'south manufacturing plant, send him out, line upward his employees, subject field them to infinitesimal interrogation, take over his books on the instant. Night piece of work was forbidden. Flight squadrons of these private coat-and-adjust police force went through the district at night, battering downward doors with axes looking for men who were committing the law-breaking of sewing together a pair of pants at night. Merely without these harsh methods many lawmaking authorities said in that location could be no compliance because the public was not dorsum of it.

The NRA was famous for its bureaucracy. Journalist Raymond Clapper reported that between iv,000 and v,000 business organization practices were prohibited by NRA orders that carried the force of law, which were contained in some 3,000 administrative orders running to over x million pages, and supplemented by what Clapper said were "innumerable opinions and directions from national, regional and code boards interpreting and enforcing provisions of the act." There were also "the rules of the code regime, themselves, each having the force of law and affecting the lives and deport of millions of persons." Clapper concluded: "Information technology requires no imagination to appreciate the difficulty the business human has in keeping informed of these codes, supplemental codes, code amendments, executive orders, authoritative orders, office orders, interpretations, rules, regulations and obiter dicta."[28]

Judicial review [edit]

On 27 May 1935, in the court case of Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, the Supreme Courtroom held the mandatory codes section of NIRA unconstitutional,[29] because it attempted to regulate commerce that was not interstate in character, and that the codes represented an unacceptable delegation of ability from the legislature to the executive. Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes wrote for a unanimous Court in invalidating the industrial "codes of off-white contest" which the NIRA enabled the President to issue. The Court held that the codes violated the U.s.a. Constitution's separation of powers as an impermissible delegation of legislative ability to the executive branch. The Courtroom also held that the NIRA provisions were in excess of congressional ability nether the Commerce Clause.[30]

The Court distinguished between straight effects on interstate commerce, which Congress could lawfully regulate, and indirect, which were purely matters of state constabulary. Though the raising and auction of poultry was an interstate industry, the Court plant that the "stream of interstate commerce" had stopped in this case: Schechter'southward slaughterhouses bought chickens just from intrastate wholesalers and sold to intrastate buyers. Any interstate result of Schechter was indirect, and therefore across federal reach.[31]

Specifically, the Court invalidated regulations of the poultry industry promulgated under the authorization of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, including price fixing and wage fixing, every bit well as requirements regarding a whole shipment of chickens, including unhealthy ones, which led to the case becoming known equally "the ill craven case." The ruling was one of a series which overturned some New Deal legislation betwixt Jan 1935 and January 1936.

Subsequent to the decision, the rest of Title I was extended until April one, 1936, past articulation resolution of Congress (49 Stat. 375), June fourteen, 1935, and NRA was reorganized past E.O. 7075, June 15, 1935, to facilitate its new function every bit a promoter of industrial cooperation and to enable information technology to produce a series of economical studies,[29] which the National Recovery Review Lath was already doing.[32] Many of the labor provisions reappeared in the Wagner Act of 1935.

Legacy [edit]

The NRA tried to end the Groovy Depression past organizing thousands of businesses nether codes drawn upwardly by trade associations and industries. Hugh Johnson proved charismatic in setting upwardly publicity that glorified his new NRA. Johnson was recognized for his efforts when Time named him Man of the Year of 1933—choosing him instead of FDR.[33]

By 1934 the enthusiasm that Johnson had so successfully created had faded. Johnson was faltering badly, which historians ascribe to the profound contradictions in NRA policies, compounded by Johnson's heavy drinking on the job. Big business and labor unions both turned hostile.[34] [35] [36]1

According to biographer John Ohl (equally summarized by reviewer Lester 5. Chandler):

Johnson's priorities became evident almost immediately. In the prescription, "Self regulation of industry nether regime supervision" the emphasis was to be on maximum freedom for business concern to formulate its ain rules with a minimum of government supervision. Consumer protection and the interests of labor were of decidedly lesser importance. To induce business to formulate and abide by codes of fair competition Johnson was willing to condone almost whatsoever type of cost fixing, restriction of production, limitation of productive capacity, and other types of anti-competitive practices....fifty-fifty with the do good of a more efficient and diplomatic management and a more tolerant Supreme Court the NRA probably would not have survived much longer. It'due south inherent conflicts and inconsistencies were merely too strong.[37]

Historian William East. Leuchtenburg argued in 1963:

The NRA could boast some considerable achievements: it gave jobs to some 2 million workers; it helped stop a renewal of the deflationary screw that had about wrecked the nation; information technology did something to improve business ethics and acculturate competition; it established a national pattern of maximum hours and minimum wages; and information technology all just wiped out child labor and the sweatshop. But this was all it did. It prevented things from getting worse, but it did lilliputian to speed recovery, and probably actually hindered it by its back up of restrictionism and price raising. The NRA could maintain a sense of national interest confronting private interests simply then long as the spirit of national crisis prevailed. Every bit it faded, restriction-minded businessmen moved into a decisive position of dominance. Past delegating power over toll and production to trade associations, the NRA created a series of individual economic governments.[38]

According to historian Ellis Hawley in 1976:[39]

at the hands of historians the National Recovery Administration of 1933-35 has fared desperately. Cursed at the time, it has remained the epitome of political aberration, illustrative of the pitfalls of "planning" and deplored both for hampering recovery and delaying genuine reform.

See also [edit]

- Job creation program

References [edit]

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-01-14. Retrieved 2011-07-05 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy every bit title (link) - ^ National Recovery Administration. The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001-07

- ^ a b Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum – Our Documents

- ^ a b Franklin D. Roosevelt Statement on Due north.I.R.A.

- ^ Carson, Clarence B. The Relics of Intervention part 4. New Deal Collective Planning

- ^ James P. Johnson, "Drafting the NRA Code of Fair Competition for the Bituminous Coal Industry," Journal of American History, Vol. 53, No. 3 (December., 1966), pp. 521–41 in JSTOR

- ^ a b c "Dollar Men & Prices". Fourth dimension. Jan 21, 1935. Archived from the original on March 4, 2007.

- ^ "The National Recovery Assistants | Economic History Services". Archived from the original on 2007-02-twenty. Retrieved 2005-12-12 .

- ^ Schlesinger

- ^ a b Johnson, Hugh S. The Blue Eagle From Egg to World. New York: Doubleday, Doran & Visitor, 1935.

- ^ a b c d Himmelberg, Robert. The Origins of the National Recovery Assistants. 2nd paperback ed. New York: Fordham University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-8232-1541-v

- ^ "Charles T. Coiner, 91, Ex-Art Chief at Ayer". The New York Times. Baronial 16, 1989.

- ^ Julia Cass (August 14, 1989). "Charles T. Coiner, 91, Painter And Noted Advertisement Designer". Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on May 21, 2015.

- ^ "Charles T. Coiner". James A. Michener Art Museum. Archived from the original on September 3, 2004. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- ^ "Charles Coiner Papers". Syracuse University Library. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- ^ a b c Schlesinger, Jr., Arthur M. The Age of Roosevelt, Vol. 2: The Coming of the New Bargain. Paperback ed. New York: Mariner Books, 2003. (Originally published 1958.) ISBN 0-618-34086-6

- ^ Krugner, Dorothy (January fifteen, 2009). "NRA buttons (from the National Button Society, U.s.a.)". Bead&Button. Kalmbach Publishing. Archived from the original on August 7, 2011. Retrieved March half-dozen, 2010.

- ^ Hamby, Alonzo 50. For the Survival of Republic. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994, p. 164.

- ^ Dan Cooper and Brian Grinder, "We Exercise Our Part: Henry Ford and the NRA," Financial History, Spring 2009, Issue 94, pp. 10–35

- ^ Sniegoski, Stephen J. "The Darrow Board and the Downfall of the NRA". Continuity. 1990 (14): 63–83.

- ^ Ronen Shamir, Managing Legal Uncertainty: Elite Lawyers in the New Deal (1995) p. 22

- ^ Shamir, pp. 24–25

- ^ Reed, Lawrence Due west. Great Myths of the Nifty Depression Mackinac Heart for Public Policy.

- ^ Arthur Meier Schlesinger, Jr. The Coming of the New Deal, Houghton Mifflin Books (2003), p. 115.

- ^ Pamela Pennock, "The National Recovery Administration and the Condom Tire Manufacture, 1933–1935." Business concern History Review," 1997 71(four): 543–68 in JSTOR

- ^ Alexander, Barbara J. (1997). "Failed Cooperation in Heterogeneous Industries nether the National Recovery Assistants". Journal of Economical History. 57 (2): 322–44. doi:x.1017/s0022050700018465. JSTOR 2951040.

- ^ Landon R. Storrs, Civilizing Capitalism: The National Consumers' League, Women'southward Activism, and Labor Standards in the New Bargain Era, (U of Due north Carolina Printing, 2000) online edition

- ^ Clapper in Washington Post, December. 4, 1934, quoted in Best, 79–80 (1991).

- ^ a b National Recovery Administration Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Car, Authority Record (Corporate Body) U.s.a., Committee on Descriptive Standards, International Council on Archives. Accessed 11 November 2010

- ^ Tim McNeese and Richard Jensen, The Smashing Depression 1929–1938 (2010) p. 90

- ^ Steven Emanuel and Lazar Emanuel, Constitutional Law (2008) p. 31

- ^ Executive Order 6632 Creating The National Recovery Review Board. March seven, 1934

- ^ come across TIME story

- ^ William H. Wilson, "How the bedroom of commerce viewed the NRA: A re-exam." Mid America 42 (1962): 95-108.

- ^ Bernard Bellush, The Failure of the NRA (1975).

- ^ Martin, Madam Secretary: Frances Perkins, (1976) p. 331.

- ^ Lester 5. Chandler, review of Ohl, Hugh Due south. Johnson and the New Bargain in Journal of Economic History (March 1987) 47: 286 DOI:x.1017/s0022050700047951

- ^ William E. Leuchtenburg, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932–1940 (1963) p. 69.

- ^ Ellis Hawley, review of Bernard Balush, The Failure of the NRA, in American Historical Review 81#4 1976 p. 995.

Bibliography [edit]

- Alexander, Barbara (1994). "The Bear upon of the National Industrial Recovery Act on Dare Formation and Maintenance Costs". Review of Economics and Statistics. 76 (ii): 245–54. doi:x.2307/2109879. JSTOR 2109879.

- Best; Gary Dean. Pride, Prejudice, and Politics: Roosevelt Versus Recovery, 1933–1938. (1991) online edition ISBN 0-275-93524-8

- Brand, Donald R. (1983). "Corporatism, the NRA, and the Oil Industry". Political Science Quarterly. 98 (1): 99–118. doi:10.2307/2150207. JSTOR 2150207. Uses corporatism model to explore the struggle between independent oil producers and major oil producers over product and toll controls.

- Burns, Arthur Robert (1934). "The First Phase of the National Industrial Recovery Human activity, 1933". Political Scientific discipline Quarterly. 49 (two): 161–94. doi:10.2307/2142881. JSTOR 2142881.

- Dearing, Charles Fifty. et al. The ABC of the NRA, (1934) 200 pgs. online edition

- Hawley, Ellis W. (1968). The New Deal and the Problem of Monopoly. Princeton Upwards. ISBN0-8232-1609-viii. The classic scholarly history

- Hawley, Ellis Westward. (1975). "The New Deal and Business". In Bremner, Robert H.; Brody, David (eds.). The New Bargain: The National Level. Ohio State University Printing. pp. l–82.

- Johnson; Hugh S. The Bluish Eagle, from Egg to Earth 1935, memoir by NRA director online edition

- Leuchtenburg, William E. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Bargain, 1932–1940 (1963) online

- Leuchtenburg, William Eastward. "The New Deal and the analogue of war." in Modify and Continuity in Twentieth-Century America (1964) ane: 81-143.

- Lyon, Leverett S., Paul T. Homan, Lewis L. Lorwin, George Terborgh, Charles L. Dearing, Leon C. Marshall; The National Recovery Administration: An Analysis and Appraisal The Brookings Establishment, 1935. in-depth analysis past economists, online edition

- Mazzocco, Dennis Westward. "Radio'southward new deal: The NRA and United states dissemination, 1933–1935." Periodical of Radio Studies 12.1 (2005): 32-46.

- Ohl, John Kennedy (1985). Hugh Southward. Johnson and the New Deal . ISBN0-87580-110-2. Bookish biography

- Schlesinger, Arthur Meier (1958). The Coming of the New Deal. pp. 87–176. online

- Skocpol, Theda, and Kenneth Finegold. "Land capacity and economic intervention in the early on New Bargain." Political Science Quarterly 97.2 (1982): 255-278. online

- Sniegoski, Stephen J. (1990). "The Darrow Board and the Downfall of the NRA". Continuity. 1990 (xiv): 63–83. ISSN 0277-1446.

- Taylor, Jason E. (2007). "Cartel Code Attributes and Cartel Performance: An Industry‐Level Analysis of the National Industrial Recovery Act". Journal of Police and Economic science. 50 (three): 597–624. doi:10.1086/519808.

External links [edit]

- 1933 Promotional Video for National Recovery Administration

- Commodity on the NRA from EH.Internet's Encyclopedia

- Archive of The Bird Did Its Part past T.H. Watkins

- Jimmy Durante singing a promotion for the NRA

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Recovery_Administration

Posting Komentar untuk "what step did the nra take to restore the nations economy"